...Best of Sicily presents... Best of Sicily Magazine. ... Dedicated to Sicilian art, culture, history, people, places and all things Sicilian. |

by Luigi Mendola | |||

Magazine Index Best of Sicily Arts & Culture Fashion Food & Wine History & Society About Us Travel Faqs Contact Map of Sicily

|

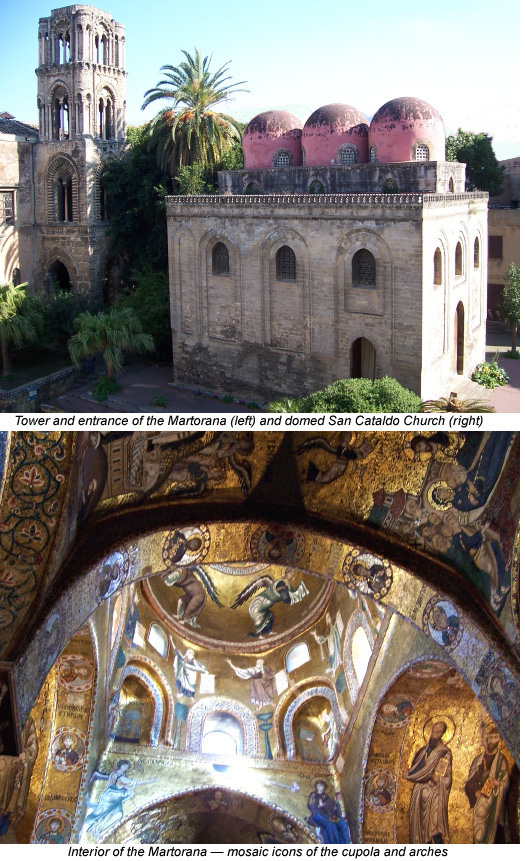

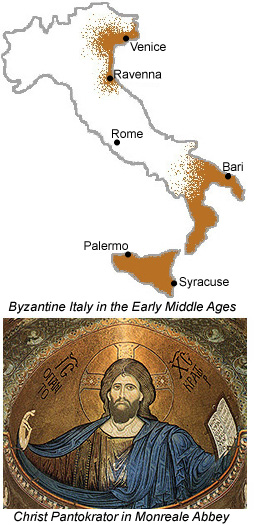

The walls of the Martorana are covered in mosaic icons, its original floor plan a simple "cross-in-square" (or greek cross) beneath a single dome. The Martorana was, in fact, built as a Greek Orthodox church dedicated to Saint Nicholas, its charter of 1143 written in Greek and Arabic. It was completed in 1151. Constructed in a fairly similar Norman-Arab style, San Cataldo has a long nave and very simple romanesque arches. This was a Roman Catholic church consecrated around 1160. Elsewhere in Sicily there are churches reflecting eclectic architectural influences. Monreale Abbey, for example, is at once Norman, Arab and Byzantine, but while it initially had an iconostasis this cathedral was founded as a Benedictine church. The cathedral of Syracuse, built around an ancient Greek temple, is a good example of a Paleo-Christian structure, though greatly modified over the centuries. There are few Sicilian churches remaining which were built explicitly for the diminishing Orthodox communities following what has come to be known as the Great Schism. Fomented for several centuries, the Great Schism of 1054 separated the Western "Roman" or "Latin" church from Eastern "Greek" or "Byzantine" Christianity, and it was a historic development inextricably linked to the Normans' conquest of southern Italy. What was the Schism and how did it alter the course of Sicilian history? How are its effects still visible today? While a detailed examination of the theological differences between what are today the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches is beyond the scope of this concise exposition, we'll begin with an explanation. Discord The Emperor Constantine legalized Christianity across the Roman Empire and the new religion spread rapidly, but in 395, in view of increasing decay, the Empire split into the West, ruled from Rome, and the East, ruled from Constantinople (Byzantium, now Istanbul). Preserving its great culture and traditions, the eastern half (or "Byzantine Empire") survived until 1453. Officially, Sicily was part of the Western Empire from 395, but following the fall of centralized power in Rome (the city was sacked in 410 and Odoacer formally assumed power in 476), a period of foreign rule by Vandals and Goths (from 468 until 535) ensued on the island. It was then annexed to the Byzantine Empire. When the Roman Empire was whole, Latin was the official tongue but even in Italy Greek enjoyed prestige as the language of learned people and was the popular vernacular in the Balkans, Sicily and the eastern Mediterranean. With the Empire divided, and the western part descending into chaos, language became divisive. Misunderstandings became more frequent because many in the West spoke no Greek, while few Greeks bothered to learn Latin. At the dawn of the Middle Ages, the distance between Rome and Constantinople wasn't only linguistic; geography itself imposed a definite obstacle, especially now that a central imperial government no longer controlled the entire Mediterranean. The patriarchs, beginning with the Patriarch of Constantinople, recognized the Patriarch of "the West" (Rome) as "the first among equals." The early church was collegial; canon law and other matters were decided by ecumenical councils rather than a single patriarch. Even among today's Orthodox, the Patriarch of Constantinople is not a "Pope." In most of Western Europe the liturgy was celebrated not in Greek but in Latin, often in the Gallican Rite. The Christians in regions from the German-speaking territories westward had very little exposure to the influence of Constantinople even though the Byzantine Empire fostered and preserved the greatest learning in Christendom during the "Dark Ages" (476-700). Nobody would compare the intellectual or artistic environment of the West to what existed in Constantinople. One need only have cast a glance toward Venice, Ravenna, Syracuse or Bari (from Rome, London or the village called Paris) to see the difference. By the eighth century Rome and Constantinople certainly had their own differences based on local practices. The Iconoclast controversy (regarding the nature and veneration of icons) was settled by the Seventh Ecumenical in 787, but though the Church remained united Rome still insisted on jurisdiction over Sicily and some Balkan territories. In general, Rome wanted the Latin-speaking territories but Sicily was mostly Greek-speaking in the ninth century when the Arab occupation began; for a few years after 660 the Eastern Emperor Constans actually established his capital at Syracuse. Beyond questions of territorial jurisdiction (in the middle of the ninth century Rome contested a Byzantine episcopal appointment in Syracuse even though Sicily was outside Papal jurisdiction) there were conflicts over certain theological teachings (in the East, for example, Saint Augustine was little appreciated) and Rome's use of unleavened bread (in the East wine and leavened bread were used in the Eucharist). A particular difference was the infamous Filioque, Rome's use of a phrase in the Creed which seemed to alter the traditional concept of the Trinity. Theological forces in Rome's jurisdiction - particularly the Franks of what are now France and Germany - pushed for Papal authority over Constantinople, something unlikely to be approved by the various patriarchates of the East (Constantinople as well as Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem). This "Latin view" was unsurprising if, in the secular realm, the Pope considered himself a king maker who could crown the likes of Charlemagne. Except for a few lengthy intervals, the patriarchs of the East commemorated (and prayed for) the Patriarch of the West and vice versa. These diptychs were thus seen as a sign that communion existed, however tenuously. Finally, in 1054, Papal emissaries to Constantinople presented an egregious letter of excommunication to that Greek Patriarch. Apart from the fact that the Pope issuing the letter had died during the emissaries' trek eastward (nullifying the validity of any correspondence), the Patriarch of Rome had no authority to excommunicate or even command his brother in Constantinople. (Only nine centuries later, in 1965, did the patriarchates of Rome and Constantinople lift the mutual excommunications of the eleventh century.) Despite the acrimony, bilateral efforts to mend the fabric of a divided Christianity continued into the next century. By the Second Crusade (in 1147), "Latins" (Western Christians) were becoming highly suspicious of Constantinople's coexistence with Islam. In the words of historian Steven Runciman, "it was after the Second Crusade that the ordinary Westerner began to regard the East Christian as being something less that a fellow Christian." In Constantinople, the "Massacre of the Latins" of 1182 was ostensibly targeted at Italian mercantile power embodied by the maritime republics' encroaching activities in that city, but the Italians' Roman Catholic faith facilitated a certain degree of Greek hostility. By the Fourth Crusade (1204), with its bloody sack of Constantinople, hopes of a reconciliation were all but destroyed. The following year a Latin army was defeated at Adrianople (in Bulgaria) and in the next few decades the Teutonic Knights attempted to conquer "heretical" Orthodox republics such as Novgorod in Russia. Enmity had become a defining characteristic of the relationship between East and West. Sicily

The Normans began their conquest of Sicily in 1061, having already conquered most of peninsular Italy south of Rome. At the beginning of the eleventh century, this peninsular region had been divided about equally between the Byzantine Empire and a number of "Lombard" feudal lords descended from the Longobards who had arrived a few centuries earlier. The Papacy encouraged the Normans' conquest of this part of southern Italy as part of its attempt to seize control of the churches which had been loyal to Constantinople. In Sicily, the popes saw in the Normans an opportunity to oust or convert the Muslims while latinizing the Greek church. Upon conquering Palermo in 1071, one of the first things the Normans did was to exile the Greek bishop, Nicodemus, to a small church outside the city, replacing him with a Latin. Apart from this gesture, the conversion of Sicily's Christians from Greek to Latin was actually a slow, gradual process. Indeed, one can hardly speak of any real "conversion" at all. Over time, Greek bishops were replaced with Latin ones while Greek liturgy was replaced by Latin liturgy. This incidentally accelerated development of a Latin-based Sicilian language. Their incursions into the Balkans and the Greek islands did little to endear the Normans to the Byzantines. Bohemond, a son of Robert "Guiscard" de Hauteville and brother of Roger I, participated in the First Crusade (1098), one effect of which was installation of Roman clergy in Palestine and other areas seized from the Muslims, but the Crusades were not an exclusively Norman affair. Indeed, the Normans rarely supported them. More significant for Italy's Greek community was the Council of Bari convened by Pope Urban II in the same year as the First Crusade. This formally established that the Greek Church in Apulia would be integrated into the Roman one. In 1143 Nilos Doxopatrios, an Orthodox cleric of Palermo, authored a theological treatise supporting the Eastern (Orthodox) church over the Roman (Catholic) influences introduced by the Normans. In the Orthodox Church there are distinct monastic communities but no large religious monastic orders. The Normans introduced the first religious order in Sicily, endowing the Benedictines with monastic churches such as Saint John of the Hermits (in Palermo) and, of course, the abbey of Monreale. Later, the military-religious orders were introduced, namely the Teutonic Knights (at the Magione in Palermo), the Templars and the Hospitallers or Knights of Malta. By the end of the reign of Frederick II (1250), Orthodoxy, such as it was, can be said to have been preserved only in a few monasteries in the Nebrodi Mountains. Two centuries later, around 1470, thousands of Albanian refugees began to arrive in Sicily fleeing the Ottoman Turks. They reintroduced Orthodoxy. Within decades, they were integrated into a "uniate" church preserving Orthodox liturgy but loyal to Rome - one of several Eastern Rites to be established within Catholicism in an attempt to convince Orthodox to embrace a "tolerant" or even "Byzantinized" Roman Church. In Mezzojuso a Greek Rite church founded by Albanians stands next to the Latin Rite one, and in 1935 the Martorana was given to the Albanian-Catholic diocese of Piana degli Albanesi. Europe While the Orthodox Church changed little over the centuries since the Schism, the Catholic Church underwent what can only be described as substantial mutations. Its theology became more rigidly legalistic and - under the influence of theologians such as Thomas Aquinas - rather more semantic and "philosophical." Artistic and architectural movements such as the Gothic and the Renaissance reflected, or at least complemented, such theological trends. Orthodox teachings differ greatly from Catholic ones regarding doctrines on what Catholics refer to as Original Sin, Free Will and the Immaculate Conception as well as concepts such as Purgatory. In practice, the Orthodox (and most Eastern Rite Catholics) administer certain sacraments, such as the Eucharist (Holy Communion) and Chrismation (Confirmation) in infancy, and permit married men to become priests - something tolerated in the Catholic Church until the Second Lateran Council (in 1139). Nevertheless, the Catholic church recognizes Orthodox orders (sacraments) and apostolic succession. Specific Orthodox views regarding certain aspects of the sacraments (and matters such as divorce in relation to marriage) differ somewhat from those of the Catholic Church, and Orthodox Canon Law (based on the determinations of Ecumenical Councils) is essentially unchanged since the Middle Ages while the more complex Catholic Code of Canon Law was fully revised most recently in 1917 and 1983. It should be remembered that Rome approached all of these matters from the same perspective as Constantinople before 1054; the inescapable fact is that in the West subsequent changes were far greater than in the East, and most were more significant than the introduction of (for example) stained glass windows and statues in beautiful Gothic cathedrals. As it is understood today, Papal Primacy, a doctrine based on a Western interpretation of scripture (Jesus' reference to Peter in Matthew 16:18), was formalized in Rome only long after the Schism. Phenomena such as rampant anti-semitism never reached the level of intolerance in the East that arose in the West, bolstered by such developments as the Inquisition. As a generality, the Orthodox do not venerate Catholic saints canonized after 1054 (Saint Louis, Saint Francis of Assisi and Saint Thomas Becket, for example) while the Catholics do not venerate those canonized by the Orthodox after that date. Some effects of the Schism were nothing short of bizarre. Even after the onslaught of the Renaissance, Italians could readily see the vestiges of Byzantine culture in the churches of Venice, Ravenna and Palermo, and perhaps in the presence of the newly-arrived Albanians. Yet, except for scholars such as Martin Luther (who recognized the nature of the split and the importance of the Eastern brethren), in the post-medieval period the average Catholic in France, England, Ireland, Scandinavia, the Iberian countries and the German lands barely had any idea that there had ever been another "parallel" church in the East, much less that the "east" included half of Italy into the eleventh century. On a purely social level, if not a theological one, such ignorance had profound effects, some of which are still with us. Historical Views For a series of events which occurred nearly a millennium ago, the Great Schism remains a remarkably contentious topic, particularly for Catholic and Orthodox zealots. Catholics generally prefer to say that it was the Easterners who left the "Catholic" church based in Rome, while most Orthodox believe that the Westerners left the "Orthodox" church and the other four patriarchs. The more objective, accurate perspective, based on the historical facts rather than the hope of not offending either camp, is that the Early Church simply divided into two parts. In the historical realm, Sicilians enjoy a cultural privilege over many Catholics and Orthodox because Sicily was for several centuries a truly multicultural, cosmopolitan society. Unlike places on the geographical and cultural periphery of important ancient and medieval events, Sicily was close to the center, and the Schism is just a single example of a complex historical legacy. If there exists a "Sicilian View" of events such as the Schism, it should be based on an impartial reading of history rather than an intentionally polemical one. Further Reading One of the most objective (neutral) general histories of the Great Schism is Steven Runciman's book, The Eastern Schism. Author of The Sicilian Vespers, he was also an expert on the Crusades. John Julius Norwich wrote an interesting chapter (numbered 8) about the events of 1054 in The Normans in the South. A pragmatic theological treatment is John Meyendorff's Orthodoxy and Catholicity.

About the Author: Historian Luigi Mendola has written for various publications, including this one. | ||

Top of Page |

Every day hundreds

of people - most of them foreign tourists - visit the church now known as the Martorana

in central

Every day hundreds

of people - most of them foreign tourists - visit the church now known as the Martorana

in central  In 1054 Sicily was under

In 1054 Sicily was under